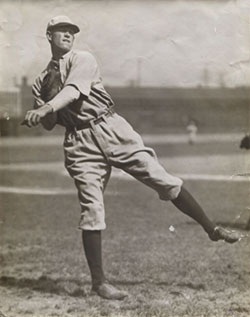

Hal Chase was one of the greatest baseball players of the dead-ball era, and one of the best of all time not to be elected to the Hall of Fame. At the end of the 1918 season, faced with a mounting baseball gambling epidemic, Organized Baseball took a hard stance to eliminate gambling from the game. Any player involved with, or having knowledge of gambling, would be subject to a permanent ban from all of Organized Baseball.

The next year, in 1919, the World Series between the Chicago White Sox and Cincinnati Reds was fixed. Testimonies claimed that Hal Chase had knowledge of what has become known as the “Black Sox Scandal.” Chase may have had little or no involvement in the plan, but he later admitted that he did know of it and regretted not reporting it. Chase was effectively banned from all of Organized Baseball after 1920. And after 1937, Organized Baseball disqualified all players, including Hal Chase, implicated in baseball gambling from being placed on the ballot for entry into the Hall of Fame.

Hal Chase was revered as the hallmark defensively at first base during the deadball era, when defense, speed, and advancing the runner were paramount. “He’s no Hal Chase” was how the media described all other first basemen throughout the first half of the 20th century.

“Prince” Hal was the first star and captain of the New York Highlanders, which became the Yankees in Chase’s ninth and final year with the club. During Chase’s nine years with the New York Americans, management cycled through over a hundred players and half-dozen managers in search of a winning combination. The only constant from 1905 to 1913 was Chase, who also managed the club at the age of 28 in 1911, a year he hit .315 with 82 RBI while excelling in the field.

After being replaced as manager for the 1912 season, Chase and New York drifted apart. Affected by nagging injuries, his play suffered, and the New York media became unkind. In 1913, the Yankees traded Chase to Charles Comiskey’s Chicago White Sox. The new scenery agreed with Chase; he led the team in hitting through the end of the season.

In 1913, discord between players and managers over salaries, the National Agreement and the Reserve Clause peaked, and a new league, the Federal League, threatened to recruit players away from Organized Baseball.

Chase vowed allegiance to Comiskey and the White Sox while simultaneously negotiating a contract with the Buffalo Blues of the Federal League (referred to as “Buffeds”). When the Buffeds played the Chifeds (Chicago Federal League Team, the Whales) in Chicago, Chase emptied his White Sox locker, crossed town, and started playing for the Buffeds.

A betrayed Comiskey filed an injunction to prevent Chase from playing with the Federal League. Chase didn’t take kindly to being corralled. He fought the injunction in court and became one of the first ballplayers to challenge the reserve clause in court and win.

Before long, the Federal League folded, and Comiskey, the most powerful man in the American League, made certain that no team in the league would offer Chase a contract for the remainder of his career.

Many have inaccurately chronicled that Chase wore out his welcome in Organized Baseball due to alleged involvement in gambling. In fact, his ostracism and relegation to outlaw status began when he challenged the oppressive forces of the National Agreement, which would dictate where and when he could play baseball.

In an interview on August 21, 1918, Ban Johnson admitted that Chase was overtly blacklisted for his attempt to defect to the Federal League and his challenge to the Reserve Clause. He said,

“Hal Chase is barred from American League baseball, has been ever since he left Comiskey’s club. It was decided then that he was wrong in his treatment of Comiskey, and our league agreed never to reinstate him.”

– Cincinnati Times-Star, August 21, 1918

After the Federal League’s collapse, Hal found a home in the National League with the Cincinnati Reds, and won the batting title in 1916 with an average of .339.

Allegations about Chase’s involvement with gambling began to surface in 1918. Gambling on the game had reached unprecedented levels, perhaps exacerbated by a shortened season due to WWI. With salaries cut, players looked for ways to shore up finances. Organized Baseball nearly cancelled the World Series. With ticket sales low, players refused to accept an offer of reduced compensation. Eventually, the players agreed to play, but rumors circulated that players made up the shortcoming by fixing the outcome of the series.

At the Winter Meetings in February 1918, American League President Ban Johnson announced that he would no longer tolerate the game’s escalating gambling problem. He announced,

“If any club owner fails to do his utmost to stamp out gambling, he will lose his franchise. If any American League player is caught associating with gamblers at any time, his immediate expulsion will follow. I mean business and I am preparing to go ahead with a policy that will suppress an evil that, unless checked, will undermine the national game.”

– Port Talk, Ed R. Hughes, San Francisco Chronicle, Feb 26, 1918, Pg. 10

During the 1918 season, Hal Chase allegedly attempted to bribe his team’s relief pitcher, Jimmy Ring, to lose a game. Betting for your own team was a common practice in Baseball, allowed by the National Commission, until 1919. Chase later admitted to gambling on games when such a practice was customary. But the allegation by Ring was unique in that, if true, it represented betting against his own team. After Ring reported the bribe to manager Christy Mathewson, Mathewson suspended Chase. Following an investigation, National League President, John Heydler, exonerated Chase:

“There was no evidence whatever produced at the trial to show that Chase had made a bet, and the only direct evidence as to his crookedness was made by Player Ring. On the stand, however, Ring was a poor witness and made statements differing from what he had stated in his affidavit, so much so, in fact, that I brought him back here Monday for further testimony. To have found Chase guilty on this man’s unsupported testimony would have been impossible.”

– Heydler letter to Herrmann, Chase File, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown

From that point forward, Heydler prohibited players from betting on any baseball game, whether for or against his team.

The exoneration didn’t necessarily prove Chase’s innocence. But it did demonstrate that no evidence ever came to light in public proving wrongdoing on the part of Chase prior to 1919.

A year later, when Organized Baseball implemented a zero tolerance for gambling, Chase learned of the fix of the 1919 World Series, commonly referred to as the Black Sox Scandal. Chase later admitted to knowing about the fix and regretted not notifying Organized Baseball. He defended himself by saying, “never had any use for a stool pigeon or a squealer.”

– The Sporting News, September 18, 1941, Lester Grant

Organized Baseball’s uncompromising resolve against gambling would seal Hal Chase’s fate. Although not officially banned, he would effectively be blacklisted, unwelcome to play in any league associated with Organized Baseball after 1920.

Some have referred to Chase as a symbol of corruption in Baseball during the era. Chase was not a symbol of corruption; Chase did not cause the rampant gambling in Baseball. Rather, Hal Chase became an example of what would come of any player possessing knowledge of, or participating in, gambling on Organized Baseball after 1918.

In 1936, the Baseball Hall of Fame inducted its first class that included Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson. Hal Chase received eleven votes, ahead of future HOFers Frank Chance (5), John McGraw (4), and Connie Mack (1). In the second year of voting, Chase received eighteen votes. He received the most votes of any player in the first two years of voting not to be eventually elected. After 1937, Organized Baseball agreed that no player implicated in gambling in Organized Baseball would again be eligible to receive votes for the Hall of Fame.

Hal Chase stated that he was wrongly accused. He likened himself to Alfred Dreyfus rather than Benedict Arnold. Dreyfus was a Jewish French artillery officer wrongly accused of espionage in 1894 who was sentenced to life in exile. The true culprit was later identified and Dreyfus was exonerated. Late in life, Prince Hal expressed regret that he didn’t have the same opportunity to be remembered as fondly as the likes of Lou Gehrig.

RELATED LINKS:

BOOKS:

How to Play First Base

by Hal Chase

The Last Stand of Outlaw Baseball

by John William Smirch

PODCAST:

Mining Diamonds Along the Border

by Mary Darling