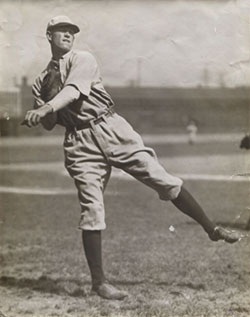

To understand Hal Chase, one must understand the National Agreement and its influence on Organized Baseball post 1900. Chase’s professional baseball career could be characterized as an ongoing conflict between Chase and the National Agreement, a conflict that ultimately would be lost by Chase. Newton’s Third Law of Physics states for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. The actions and reactions between Hal Chase and the National Agreement would shape Prince Hal’s professional life and ultimately shape his legacy.

From the moment Hal Chase was drafted by the New York Highlanders in 1904, he was innocently and unknowingly thrust into the burgeoning conflict between minor league and major league baseball due to the practical implementation of the National Agreement that went into effect just a year prior.

1904-1905: Hal Chase’s First Year

In 1904, Chase played for James Morley’s Los Angeles Angels, a minor league team in the Pacific Coast League. Morley knew that the Highlanders planned to select Chase in the November 1 draft. According to the National Agreement, Morley would be compensated $750. Morley concocted a plan to auction Chase to the highest bidder before the draft. But unbeknownst to Morley, Organized Baseball moved the draft to September 15, and Chase was scooped up for a quarter of his value.

Morley vowed to keep Chase the following year and petitioned the other Pacific Coast League (PCL) owners to stand up to Organized Baseball. In January, Hal Chase’s brother passed away; Chase stated in the press that in spite of the National Agreement, he preferred to remain in California and not play for the Highlanders.

Even if Chase couldn’t ultimately play for Morley, whose team was in the PCL that operated within the National Agreement, Chase could perhaps play in the California League, which operated as an “outlaw” league, separate from Organized Baseball. He had played for the California League’s San Jose team in the offseason prior to the 1905 regular season.

Hal suited up to play with the Angels in March, as late as March 11, after the Highlanders had started playing in the spring. Many star players in the PCL refused to sign for the next season until the owners resolved the issue with Chase.

The Pacific Coast League initially sided with Morley and vowed to secede from Organized Baseball over the Chase affair.

The Highlanders threatened that Chase would play for them or he would play nowhere. Griffith told reporters on March 22:

“Chase got our advance money, and now it is the New York Americans or nowhere for him. This nonsense has gone far enough, and I am tired of it… If Chase plays with Los Angeles, it shall be under open war conditions, and I guess the big clubs, which are making money hand over fist, can stand such a war better and longer than one little minor affair out in California. It is generally felt that if Chase doesn’t report, the bitterest baseball war in the history of the game will shortly be precipitated.”

– Will Make Chase Play, Direct Wire to the Times (New Orleans), Mar 23, 1905, II3

The same day the papers reported the challenge from Griffith, Chase and Morley announced they had come to terms on a contract for 1905. For the next week, tensions ran high throughout the PCL. Less than a week after Chase signed with Morley, the PCL owners conceded to the forces of Organized Baseball and the National Agreement and instructed Hal to join the New York Highlanders.

Even before Chase started his first full major league season, he was steeped in controversy over contract issues. The controversy, however, was external to Chase. He just wanted to play ball. Nearly every season of his career, Chase would threaten to jump his contract to play among family, friends, and appreciative fans in California, seeking refuge in the Pacific Coast League and California League, often in opposition to the National Agreement, as an alternative to playing in the East.

1906-1907: Exhibition Games Condoned

After the 1906 season in which Chase hit .323 for the Highlanders, who finished second in the American League, Chase returned to California for the final games of the independent California State League season that pitted Chase’s San Jose Prune Pickers and future Hall of Famer Frank Chance’s Stockton Millers in a battle for the title. Many major leaguers joined each team down the stretch. After the California State League Playoff concluded, Chase and Chance assembled teams, largely comprised of professionals bound by the National Agreement, to face off in three exhibition games in Los Angeles. The newspaper reported the results as Chance v. Chase: Actual Box Score from December 30, 1907

Owners had yet to voice objections to players joining teams in the offseason. But that sentiment would change in subsequent years when minor league teams that were under the National Agreement complained that their rival leagues in independent leagues would out-draw them at season’s end when they stacked their teams with major leaguers.

Prior to 1907 season, Pacific Coast League teams courted Chase, but none wanted to challenge Organized Baseball. He fielded offers from the “outlaw” California League’s San Jose Prune Pickers seeking an increase from his $1,500 salary to $4,000. He allegedly negotiated a similar offer from an outlaw team in Los Angeles. Ultimately Chase accepted an increase to $4,000 per year from the Highlanders.

1908: Owners and National Commission Begin Opposing Outlaw Leagues

After hitting .287 for the Highlanders in 1908, Hal Chase returned once again to play for the San Jose Prune Pickers in the California State League. Pacific Coast League President, Cal Ewing, responded by attending the National Association meetings to protest the practice of major leaguers participating in California State League late season games.

The National Commission immediately issued an order forbidding all National Agreement players from joining the outlaw California State League. The Commission warned that any violations would result in a fine, suspension, or ban from Organized Baseball. Chase had already played in three games before the announcement. But after the announcement, the irreverent Chase continued to play – on October 30, demonstrating a playful sense of humor, he played under the assumed name “Shultz.” He fooled no one and outraged President Ewing.

Chase hit .800 over the twelve-game span and thrilled fans with his dazzling defense. He indicated, once again, that he would remain in California and not return to New York. Highlander management showed little concern, and Chase was the first to report to spring training for the Highlanders.

Baseball Wars of 1909

At the end of 1908, Hal Chase once again found himself at the center of controversy resulting from the conflict between the National Agreement, minor league baseball, and his desire to play in California.

Upset with the Highlander Manager, Kid Elberfeld, during the 1908 season, Chase stated that he had enough and couldn’t continue playing. He abandoned his team and signed with the Stockton Millers of the California State League at the beginning of September for their final twenty-three games for a salary of $1,000.

At the same time, a baseball war emerged throughout the country as openly defiant minor leagues, including the Pacific Coast League (PCL), threatened to operate as “outlaws” throughout the country in direct competition with Organized Baseball. Hal Chase found himself in the middle of a contentious battle between Organized Baseball and the minor league franchises on the West Coast, including teams from the California State League and the Pacific Coast League.

The PCL and California State League considered merging and operating within Organized Baseball. Chase was under contract to play for the Stockton team, a California State League powerhouse. The Stockton owner, Cy Moreing, adamantly opposed joining Organized Baseball, and courted other franchises, including those within the Pacific Coast League, to join him.

On December 2, the league owners of both leagues met in San Francisco. American League President Ban Johnson and National League President Harry Pulliam boarded a train to meet with owners.

During the trip, Ban Johnson met with Hal Chase to convince him to return to the New York Americans, which had hired George Stallings as manager. Ban Johnson and Stallings had been adversaries since the formation of the American League, at which time Stallings, then a minority owner of the Detroit Tigers, negotiated to defect to the National League. Johnson removed the traitor Stallings as owner and vowed that Stallings would never be welcome in the American League. Yet, the Highlanders hired him to manage the team in 1909. Chase had aspirations to manage the Highlanders. Johnson may have indicated that if Chase returned, he would make the case for Chase to replace Stallings as manager the next season. In fact, that is what happened. The next year, American League President Johnson pushed out Stallings, and Chase took his place.

Chase, the star of the Highlanders, was considered the answer, not the problem. He returned to play for the Highlanders in 1909.

After Elberfeld’s team performed miserably the second part of the 1908 season, with or without Chase, Elberfeld was fired. Upon examination, management discovered that the team suffered from internal strife not caused by Chase. In hindsight, New Yorkers became sympathetic of Chase, his trouble with Manager Elberfeld, and his reasons for abandoning his team.

1913: Chase Defeats National Agreement and Reserve Clause

Chase was traded from the New York Americans, by then called the Yankees, to the Chicago White Sox in 1913. During the offseason, Chase joined two teams of All Stars, largely filled with players from the New York Giants and Chicago White Sox, on a world tour of exhibition games. White Sox owner, Charles Comiskey, joined the tour. Like Chase, Comiskey had a reputation as a penultimate defensive first baseman as a player in the major leagues. He and Chase got along exceedingly well, Comiskey playing the role of guardian and mentor, as well as proud owner of his team’s new star.

During the tour, the Federal League was rapidly forming and players on the tour, including Chase, were approached and recruited. In 1914, amidst an abundance of defections by many major league players to an alternative professional league, the Federal League, Chase reported to play with the White Sox and pledged to be loyal to Comiskey.

During the 1914 season, Chase defected to the Buffalo Blues of the Federal League. Comiskey filed an injunction preventing Chase from playing outside of Organized Baseball. Chase successfully fought the Reserve Clause, his status as property of Comiskey’s White Sox, and the power of the National Agreement in court. He was allowed to continue playing with the Buffalo Federals.

Because Chase won his contest against Organized Baseball and Charles Comiskey, Comiskey vowed that Chase would never again play for a team in the American League.

1916: Chase Finds a Home in the National League

After 1915, the Federal League collapsed. In 1916, Chase became a free agent, but was still under contract for $8,000 with the wealthy Harry Sinclair, a financier of the Federal League. Chase attempted to negotiate returning to California to play for the Pacific Coast League’s San Francisco Seals. The Pacific Coast League had a $4,000 salary cap, so Chase proposed that the Seals pay the $4,000, and Sinclair make up the difference with the remaining $4,000. In the end, the Cincinnati Reds of the National League signed Chase, and he reported on time (and led the league in hitting).

1919: Dispute over Unpaid Wages during Suspension Stemming from Accusation of Gambling

In 1919, Chase was cleared by National League President of any wrongdoing associated with the alleged bribe of Cincinnati Reds teammate Jimmy Ring and the subsequent suspension by Manager Christy Mathewson. Once cleared, Chase demanded payment for the portion of his 1918 salary that was unpaid due to his suspension. In the end, the New York Giants, which signed Chase, agreed to compensate him for wages not paid by Cincinnati. Cincinnati vowed never to hire Chase again.

Contract Disputes in Conclusion

In modern Baseball, a player’s reputation would be unaffected by negotiations he had with management. But in the dead-ball era, Chase was sometimes unfairly portrayed as trouble due to his irreverence and resistance to the National Agreement and the reserve clause.

His preference to play outside of the influence of the National Agreement, in California or the Federal League, should not contribute to nor support any derogatory narrative of Hal Chase. In fact, Chase’s opposition to the oppression of the Reserve Clause would be considered by today’s standards, in the context of the labor struggles in America, as brave and heroic. Chase didn’t see himself as a hero, however. He resisted because he wanted control over where and when he could play baseball.

RELATED LINKS:

BOOKS:

How to Play First Base

by Hal Chase

The Last Stand of Outlaw Baseball

by John William Smirch

PODCAST:

Mining Diamonds Along the Border

by Mary Darling