To understand Hal Chase, and the era in which he played, one must understand the formation and impact of the National Agreement, which took effect in 1903, just a year before the New York Highlanders drafted the twenty-year old Californian.

Prior to 1903, organized baseball experienced decades-long financial difficulty sometimes caused by player mobility between franchises and competition between leagues. The National Agreement represented a peace accord between the American and National leagues. At its cornerstone was the “protection of the property rights of those engaged in baseball as a business.”

Ban Johnson, president of the American League, and Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey, were two of the National Agreement’s founding fathers. They would oversee the interests and the welfare of the American League for the next two decades by enforcing the National Agreement and by preserving and promoting the success of all of the league’s teams.

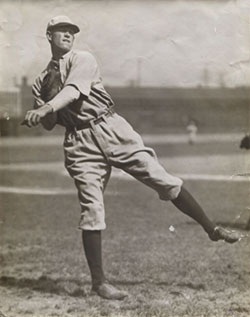

Hal Chase would become the franchise player of the newest team in the League, the New York Highlanders. Other franchise players of particular importance in the American League after 1903 included future Hall of Famers Eddie Collins (Philadelphia Athletics), Ty Cobb (Detroit Tigers), Tris Speaker (Boston Red Sox), Nap Lajoie (Cleveland Napoleans), Ed Walsh (Chicago White Sox), and Walter Johnson (Washington Senators). American League President Ban Johnson would take a keen interest in any issues related to the franchises, and these players in particular.

Players that were under contract were considered the property of their respective franchises. Clubs that harbored players under contract were considered “outlaw” organizations. Salary limits were agreed upon by all teams, and minor league clubs were required to relinquish drafted players in exchange for an established fee.

Over the next two decades, the National Commission would exert an absolute and oppressive force over major league and amateur baseball. It would be the source of conflict, animosity, legal proceedings, and sweeping negative repercussions. It would, however, bring financial stability to Organized Baseball.

The National Agreement was an administrative construct managed by the National Commission. The Commission represented the interests of the owners. It didn’t prowl the territory to catch barnstorming major leaguers in the act of sedition. Rather, those bound by the National Agreement submitted the names of players in violation of their contracts. The Commission acted to enforce the rules at the request of the owner. Whether a player was “banned” was often a function of an owner’s desire to pursue the ban. In the end, the good players were often given a leniency that others with diminishing skills did not receive.

The Commission effectively created and preserved a monopoly for the owners, protected the property rights of the owners, and enforced a “blacklist” of those who acted in opposition to the objectives of the Commission and Organized Baseball. Organized Baseball’s unfair practices, etched in stone in the National Agreement, would continue for decades with the vigor and collective power of baseball owners.

The Reserve Clause was the clause in player contracts that bound the player to one team to preserve ownership’s property rights over the individual.

Salaries were determined by the owners; no negotiation took place. Whatever an owner wanted to pay, the player had to accept. Players grievances also included not being paid for spring training; being required to pay their fare to spring training, when traded, or sent to the minors; getting their pay suspended when injured; and having owners make public any grievances between player and owner (player vilified in press).

RELATED LINKS:

BOOKS:

How to Play First Base

by Hal Chase

The Last Stand of Outlaw Baseball

by John William Smirch

PODCAST:

Mining Diamonds Along the Border

by Mary Darling